The Cafe Girl Read online

Page 2

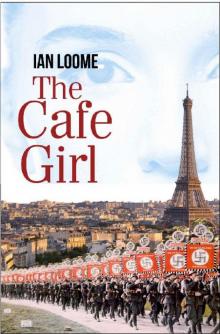

Nothing seemed able to quash the city's spirit. Despite strict rationing, the umbrella-dotted cafe patios along the left bank of the River Seine were still busy; Giraud strolled past them, silently judging patrons who chatted and drank wine with German soldiers in formal dress. Most were just there to relax and watch the barges roll by.

He passed the willow trees and ornate flowerbeds of the Tuileries Gardens. Patrons in suits and long dresses strolled to admire the topiaries and blooms, sipped wine, and debated the politics of the Petain administration, the new nationalist government that collaborated with the Germans from Vichy.

Lovers still embraced tenderly while picnicking or walking the city's narrow lanes. The five-story Haussmann Apartment blocks that helped to define the Paris skyline were untouched by bombing or strife, their oddly angular mansard roofs in dark slate grey giving the city its strange, elegant uniformity.

He did not venture as far north as the Eighteenth and Tenth Arrondissements, where the red light districts thrived. But after an hour of glancing around occasionally and losing his focus continually, he realized he was a mile from anywhere that the bike might realistically be located.

He tried to remember which route he'd taken to Le Marais. He'd started the day just a half-hour's ride north, in his office within the small city suburb of Saint Denis. It was a hard-scrabble town; factory workers in denim overalls and caps kept conveyors running and the smokestacks burning, while Algerian and Turkish immigrants called out their prices for spices and rugs from carts and booths on narrow, gloomy streets.

Eventually, he'd backtracked to his starting point and, one block north of Rue Rivoli, he'd found it, not attached to a bus pole, as he'd left it, but discarded in an alley. It seemed otherwise no worse for wear, and he'd climbed aboard to begin peddling west, toward his favorite lazy haunt, the Bar Figaro in the Eighteenth.

It was a quiet day and peaceful.

Giraud prayed that it would remain that way until the night time came. Then he prayed for his fellow officers who would venture out after dark. The nine o'clock chimes from the bells of Notre Dame Cathedral and Basilica Sacre-Coeur would echo across Paris. The power would go out and the City of Lights would be plunged into blackness.

The Nazi-imposed curfew would take over, redirecting electricity away from the city and to the war effort, and draining Paris simultaneously of its vitality.

For most, it was foreboding. Those same tall apartment blocks cast slithering shadows across the broad boulevards, a blackness that oozed between the cracks of the paving stones, the stillness punctured only by the hard heels of German jackboots, the odd whistle, a bellowed demand or fatal gunshot. The sole benefit was to those who had need and permission to venture out? They could no longer see the gigantic inverted Swastika flags that hung from the Eiffel Tower, the Arc de Triomphe, and every major government building.

Giraud's authoritarian side appreciated the power of the curfew, even as his gut told him that nothing could be more wrong than Frenchmen being ordered about by Germans. Even during the day, a veil of apprehension covered every engagement like a thin sheet of January ice. The elegance of the Belle Époque and post-Renaissance Paris, the artistry of cubism and impressionism, the passion of debate: these things still existed but as pale imitations of themselves. And so it was that most Parisians felt but a small measure of what it truly meant to be French. Their anger simmered and their resentment spread, whispered promises of retribution between back row students, tired bureaucrats and angry street vendors. For many, it had all become simply too much to bear.

For many... but not for all.

For a select few, the war was not an imposition, or a moral outrage.

It was merely a matter of opportunity.

For Giraud, the harsh conditions created stress… but also welcome, enriching ventures.

He had risen during sixteen years to become the number two in command of the Saint Denis police precinct, one of Paris' busiest suburbs and home to many factories and immigrant workers.

He had a renaissance-era three-room apartment in the nearby Tenth Arrondissement with plush purple carpet and beautiful green patterned wallpaper; he had access on the black market to everything from caviar to cuts of beef and fresh vegetables; and he had certain avenues for improving his finances that, while risky, were unlikely to attract too much attention. After all, most people tacitly approved of those who could offer some vice and relief from the tensions of war.

He had yet to find a wife, and he still felt a timid embarrassment, a rising flush in his face when a woman chanced to catch his eye and smile. His foster mother had taught him to assume ill-intention on the part of the flirtatious, due to their un-Catholic nature, and he had been accosted by a brazen woman when he was thirteen, taken into the dark of a movie cinema while she fondled and tugged at him.

But even without love, he knew how much better off he was than most of his compatriots, and that sense of privilege made him happy. His efforts were paying off, he told himself, and he had been elevated in society as a consequence.

He headed south into the Eighteenth along Boulevard Barbès, his bicycle passing a horse and cart.

The road was deserted aside from the odd other cyclist. Cars were parked at home or sold, because gasoline was rare; when they were driven, they often were adapted in outlandish style to use vegetable oil or other lesser fuel sources like sewer methane; conversion motors and storage tanks were perched on roofs or stashed in trunks, their storage tanks like stranded torpedoes. The buses were also in shorter supply, though still running, and the metro was usually dangerously overcrowded.

Paris had always been a physically small, walkable city -- the bicycle ride from St. Denis to the Eighteenth was a mere half hour -- and there were plenty of pedestrians dotting the sidewalks and crossing at corners. Giraud found it easy to get around, almost peaceful. It felt a little backward, it was true. He wondered if the roads would return to the overcrowding and congestion of Paris' thriving pre-war days once the Germans won the war with the British.

And victory seemed likely. The sheer demand the Germans were placing on the factories in Saint Denis and other suburbs suggested production of vehicles and equipment for the army could barely keep pace; shifts worked around the clock, and some even brought in part-time help from the nearby internment camp. The army's request list continued to grow, from fuel to leather to vehicles, and growth suggested progress.

It wasn't that he trusted the glowing radio reports on the Germans' vast superiority, or anything else the broadcast propagandists said, for that matter -- Giraud was ambitious but not a complete fool. It was the sheer pillaging of French resources and the Germans' decision to invade Russia just months earlier. To the average Parisian, with limited access to accurate reporting from the frontlines, there seemed little doubt that Adolf Hitler's Third Reich was rolling over the rest of the continent with the same ease as Belgium, Poland, France and Czechoslovakia.

And as he cycled along, he saw fear and disillusionment on the faces of the old lady pedestrian, the grey-mustachioed leek salesman behind his wooden push cart; he stopped as he so often did at the same newspaper kiosk, where the ginger-haired, once-obese newspaper vendor had been reduced by rationing to just mildly plump.

The vendor gave him a nod as Giraud debarked his bicycle and propped it against his right side so that he could order. 'Morning, deputy superintendent,' the man said. 'Same as usual?'

'A pack of Gitanes and the paper, please, Mr. Gauvreault. And how has your day been so far?'

'Well, you know... I'm on my feet all day, and my poor arches certainly do suffer for it,' the man said as he placed the cigarettes and paper on the counter.

Giraud was about to pick up his purchases when he stopped and made a show of reaching for his wallet. 'Oh... how much is that?'

The kiosk operator held up both palms. 'Don't be foolish, sir, your money is no good here.'

Giraud tipped the fresh pack of cigarettes at the man as if doffi

ng a cap. They went through the ritual every day, and the policeman always felt a pang of empathy for the common man and his struggles when he acknowledged Gauvreault's daily grievances. People like Gauvreault had the least to defend but also the least ability to do so; they were those who took the brunt of life like a relentless, eroding pressure from above, liquefying their hopes and dreams. He saw the kind of fatigue that sets into the bones when optimism has begun to vanish, leaving stooped shoulders and forlorn expressions.

He had sympathy, but little time for altruism. Most of the disheartened and downtrodden were there precisely because they had not as yet been stranded at the bottom, where they would be required to claw their way to a better life, he proposed. That would change soon enough. A few more years of war would see to it. They would toughen up, as he had, and learn their place, or how to rise above it.

A black Nineteen Twenties Daimler full of uniformed Germans passed on his left, the engine chugging away on diesel, its spoked tires barely brushing past him as if he wasn't there. He wondered where they were headed, whether their duties for the day would involve the usual casual, brutish violence. Even French people who approved of the fascists and their claim of traditional French values were put off by their haughty, arrogant confidence, the way they took every opportunity verbally to belittle their hosts and praise their own. Giraud supposed much of it was just their accent, the way it made everything seem formal. Perhaps, he supposed, it was a sense of cultural inferiority; what had the Germans ever produced, after all, aside from sour beer and autocracy? What was it his Nazi associate Gunther Obst had proposed the last time they talked? That Paris' winding, cobbled alleys and narrow streets were 'impractical and in drastic need of widening'? The Nazis preferred the sterile uniformity of Hitler's architect friend, Albert Speer, or his designer, Hugo Boss. He suspected they also cooked without butter and put the cork back in the bottle so that they could save some wine at dinner.

He leaned into a right turn at Boulevard de Rochechouart, bicycle tires bouncing gently on the gaps between paving stones, reminding him that they needed a little air. On the corner sat a black flagpole with a promotional flag run up to its top for a propaganda photo exhibit by the Germans, a cartoonish 'Shylock'-style depiction of a hook-nosed man in a kippah, with the headline 'The Jews In France.' He had no quarrel with the Jews, but neither did he wish to associate with them. It seemed utterly disadvantageous.

Giraud would take advantage of the unseasonably warm weather and he would cycle up Rue La Fayette and Boulevard de Magenta, past the Haussmann blocks, into the Eighteenth. He would roll by baroque and renaissance buildings, each street lined with trees about to lose their leaves, to the cafe he had frequented for the better part of two years, a haven for writers and thinkers, a quiet place in the midst of a world at war.

But, on this day, it was not so quiet.

3…

Giraud tried to appear stoic as he stood behind his bicycle and examined the occupants of the patio. Men in short-sleeves, caps, neckerchiefs and pantaloons, lounging around the tables as if the concept of work did not exist. One with his knee up and foot on a chair, as if it were his own kitchen. Two others attempted to bounce a ten-centime piece into a cup of beer. Another was asleep, with his head on the table.

Giraud frowned. He did not recognize any of them. Transition was not Giraud's forte; he preferred predictable circumstance, safe familiarity. He preferred to write in peace, surrounded by older patrons or pretty waitresses. These young men looked tough and bored. He peered into the shaded interior of the open-fronted cafe, which sat at the corner of Boulevard Poissonniere and Rue Montmartre. Two more delinquents were seated just inside the door, playing cards with the deck perched at table's edge, next to a blue paper packet of Gauloises cigarettes.

Where had they come from? Why his cafe and on such a laborious week, when he needed calm and the flitting of ink pen across paper? Attempting to lose himself in his writing would be impossible, Giraud supposed, if he was constantly worrying about what they were up to, or forced to listen to their nattering.

The older barman, a thick-joweled, ruddy nosed, steel-haired veteran named Eric, was wiping down glasses at the back of the place, then hanging them from the rack above the bar. Water dribbled onto his mound of a belly, under the green bar apron. He looked around for a moment and his gaze seemed to meet Giraud's, before travelling back around the room. If the new business was irking him as well, he did not show it.

Perhaps they were working in the area and would only be there temporarily, Giraud thought. But they did not seem like working men; the indolent body language suggested they had no intention of picking up a shovel or even a pen any time soon. He tried to think of a reason to use his authority in order to roust them but nothing came immediately to mind. They were not doing anything wrong, and there was nothing he could invent without potentially serious consequences. So he leaned against his bicycle, one hand on the handlebars, the other on the seat, feeling an anxious tingle throughout his body, the stomach-fluttering discomfort that comes from losing the best laid plans.

'I believe I know how you feel, monsieur,' a young voice to his left pronounced. 'They are a most unwelcome group.'

Giraud glanced that way. Young Pascal had introduced himself two weeks earlier; a dark-haired, fair-skinned orphan in shorts who said he was living with his uncle, Pascal could not have been more than twelve years old. He'd told Giraud how much he admired his uniform and badge, and how grateful he was for a strong police presence in Paris. He'd mentioned his uncle's lessons, and how he'd learned there was nothing more important than the fight against communists.

The boy just wanted company, Giraud knew. Thousands of children had been evacuated from the city to the unoccupied south just before the invasion and there were few others around the neighborhood.

'Who are they, Pascal?' Giraud asked. 'Are they students? Or perhaps radicals?'

'I think the latter,' the boy said. 'They have come for two days -- while you were away for the weekend -- and do nothing but drink, smoke cigarettes and argue. They seem loud and stupid, monsieur. '

If Eric had managed to find some good coffee, rather than the chicory substitute they usually stocked, then the new faces would be understandable, Giraud thought. Unfortunately, such was not the case. 'Well, this will not do at all,' he said.

'You planned to write poetry today, monsieur?'

'Along with some fiction, yes,' Giraud said. 'I found great inspiration in watching the different types of traffic that traversed the boulevard.' He glanced backwards as if to illustrate the point, as a horse-and-buggy clopped slowly by. 'But now I sense a tension...'

'It is probably because of the Freemasons,' Pascal said. 'My uncle has told me they meet in the apartments above this place on weekends.'

'Really? Freemasons?' That was not a group with which any man in Paris presently wished to be publicly associated. The Nazis had made their disdain for Freemasonry clear.

'Yes, monsieur.'

Giraud felt pensive and his stoic exterior dropped for a moment, a sense of defeat settling in. 'And now these hooligans. I suppose it is all too much.'

'Perhaps they will leave if you take up a prominent table,' Pascal suggested. 'They do seem to be the types who would not get along with the law.'

Giraud considered the idea but for barely a moment; the last thing he needed was for word to get around that he bullied people. Both policing and the black market relied on trust, and no one trusts a bully due to the inherent selfishness of the act. 'No, it's best if we leave them alone. For now, I shall be forced to find somewhere new for inspiration. Perhaps when they tire of the place or Eric chases them off I will return.'

Pascal looked up brightly. 'I know a good spot, monsieur: there is a small park just a few blocks from here, off the main boulevard. It is very quiet, although perhaps too quiet to offer the inspiration you seek...'

Giraud did not have an immediately better idea. He had managed to place at least three d

ays' work upon his most trusted officer, a go-getter who had been grateful for the extra files, despite the city's endless torrent of crime. The time he had intended to occupy at the cafe writing would not fill itself. 'How far is it?'

'Less than a kilometer, I think. No more than two.'

'Okay, let's go. I will push my bicycle, so that you do not get left behind.'

The young man smiled and nodded, and they headed off down the sidewalk to the next corner, onto Rue Eugène Sue. The air was cool, but the sheer volume of horse dung on the street made Giraud wrinkle his nose. 'Have you considered what we discussed last week?' Giraud asked the young man as they walked.

'Yes, for sure,' Pascal said. 'But I do not believe my uncle would agree, even if he could raise the money you seek.'

'You would be much safer outside of the city,' Giraud said. 'You know this is true.'

'Yes, and as I have said, my uncle speaks of nothing except his love for Paris and his hatred for the communists. I think I would get a real scolding.'

Giraud grimaced. He did not want to hear about the uncle's disciplinary repertoire. Personalizing such relationships did not blend well with the needs of the time. If the boy's uncle was more than a prospective source of finance, he was a personal problem. And Giraud did not take on personal problems.

'Best to leave it be for now then,' Giraud counselled. 'Perhaps if he becomes more nervous about the English and bombing, we may revisit the situation. In the meantime, show me this place, this park you admire so much.'

4...

When Insp. Paul Vaillancourt finally stirred from his night's rest, he found his wife Caroline perched on the edge of their double bed, watching him with a placid, peaceful look upon her face, a few strands of blonde hair falling over her right eyebrow.

'Good morning, my love,' he said, squinting against the bright light of the midday that streamed through the apartment's twin skylights. He scratched his thin beard, more a ten o'clock shadow than the real thing. Caroline wasn't fond of it, but he felt it covered up how chubby his cheeks looked and drew the eye away from how broad and round his face was. 'A centime for your thoughts; you look enraptured with love for me.'

The Cafe Girl

The Cafe Girl