The Cafe Girl Read online

Page 5

'I don't know how you signaled your friend here, monsieur,' he said to the beefy kiosk owner, 'but I don't think he'll do much good to you without this.' He held up the pistol for both to see. 'Now, are we going to have a pleasant conversation? Because if not, I can have my men at Station Fourteen go see what they find in the back of that kiosk of yours.'

The kiosk owner's eyes flitted to his companion.

'Alone,' Vaillancourt said. He nodded at the other man. 'Go on, get out of here, before I arrest your sorry soul.'

The thug bolted out the door. Vaillancourt reached back and swung it closed. 'Now, monsieur: about your cigarette business.'

6...

Pascal had long since become bored and wandered off by the time Giraud finished writing, and the cafe patrons had come and gone, with dusk settling in over the city.

The piano player was still there, though. He was interpreting Gustav Holst, Giraud noted, which was risky, as the Nazis were no fonder of English music -- technically -- than of jazz. But the policeman also knew it was an obscure classical composition and it was unlikely that anyone would notice.

Giraud pushed his bicycle to the curb and onto the street, mounting it and pedaling in one smooth motion. He gave the piano player a curt nod and the man glanced back but did not pause. The policeman took the first hill street, to the cafe's right, and his tires bumped and bounced over the pothole-strewn road.

The sun was low in the sky, and already the cathedral-tall apartment buildings cast long shadows across the streets and sidewalks, their contrast with the greys of the city muted by the lateness of the day. Traffic had been reduced to near none, save for other cyclists: a woman with a basket of onions; a man in a suit and bowler. Curfew was still three hours away, but most people had already gone home for the night, to try to piece something meager together for supper. The absence of working street lamps along the route meant that by the time he reached the office of the Ministry of Agriculture and Supply, it would be menacingly dark.

Not that it really mattered. Giraud had taken the route so many times over the twelve months prior that he believed he could have pedaled it with his eyes closed. He passed Jerome's newspaper kiosk, where the old man sold copies of Paris-Soir by the bundle and copious blue packets of Gauloises and Gitanes, the dark tobacco's pungent aroma ever-present in the city air; he passed the Moulin Rouge, where the can-can dancers had been made to cover their nipples, but the champagne continued to flow at exorbitant rates. He pedaled by the steps down to the Metro at Place Clichy, where crowds of commuters took advantage of one of the few remaining cheap forms of transportation; he cut south along Rue d'Amsterdam and Rue Tromchet, across the river to the Quai 'Dorsay, where the cafes afforded shoppers a view of the Seine once partially blocked by artists and vendors, most unable to make a go of it under rationing. He passed the neoclassic Palais Bourbon, with its Romanesque columns and a line of Mercedes limousines outside, each having doubtless conveyed a high-ranking Nazi to the seat of government. He cut across traffic, pedaling quickly to avoid oncoming cyclists, and along Rue de l'Université.

The ministry building would be nearly empty, he knew. But his contact, Francois, would not want him to venture inside and be seen nonetheless.

For a princely sum of ten thousand francs for the calendar year Nineteen Forty-One, Francois provided Giraud with extra ration cards for tobacco, chocolate, milk, meat and vegetables whenever he needed them.

When food wasn't the issue, he was a valuable conduit for pilfered goods of all sort. After the Germans took control, Giraud had campaigned for and received special appointment as go-between for all regional police and the Sicherheitsdienst, or 'SD', the Nazi SS intelligence unit. His superiors showered him with commendations and authority over the liquidation of all public asset seizures. And yet, content as they were with securing their own privileges, they paid little-to-no attention to his actual behavior. There was barely a day that passed when Giraud was not out of the precinct office, attending his own affairs after first delegating to those below him. He was a creature of opportunity, and the black market was like a newly invented game, where the rules weren't quite clear.

Just like his job, its flexibility appealed to him. It felt liberating; the requirement that most business be completed below board, with the right people compensated and the right favors proffered meant new opportunities lay around every corner for those brave enough to seize them. Yes, he was a policeman. Yes, he was a writer, a poet, a lover of fine wine. But above all, he fancied himself a survivor and a capitalist, a self-made individual. He had been granted nothing in life, and he offered little back. To date, it had seemed a fair exchange.

And so Giraud pedaled his bicycle around to the rear of the building where a small lane lit by a single street light led to the parking areas for several other neighbors as well. Francois was waiting at his usual shadowed spot along the wall, away from the back door. He had on a wool overcoat and beret; when combined with his owl-like round spectacles and a moustache trimmed like Hitler's, in a small patch under the septum, it made him look like der Fuehrer's younger, chubbier brother, Giraud decided. But then, that likely served his purposes, given how much time he spent dealing with their ambitious overlords. Perhaps it unnerved them that Francois brayed 'Heil Hitler!' even more enthusiastically than they did.

'Good evening, my friend,' the bureaucrat said as Giraud wheeled to a halt. 'Did you find what I asked for?'

Giraud reached inside his jacket and withdrew a brown paper package the size of his hand. 'This was not easy to get.'

'I don't doubt it. The coroner is meticulous about cataloguing personal belongings. He does not wish to share his predecessor's fate, no doubt.' Francois took the package and secured it within his coat.

'He said the family insisted upon coming back several times to demand the broach. Something about it being an heirloom.'

Francois shrugged. 'If you believe the Nazis, it cost someone his life. That is probably why.'

'Because he married a Jewess.'

'Not wise in this climate.'

'But not a reason someone should die.'

'No. No, it's not.' Francois peered at his colleague in the dark. 'And when Hitler promotes me to the head of his combined forces, I shall make note of that. You are not getting soft on me, are you, Giraud? I'd hate to think I need to worry about you. You've always been remarkably dependable.'

'No. No, of course not. I'm fine. How did you know it would be there?'

'The gentleman who tipped off the Nazis to the wife. He wants a cut, of course, which is going to have to come out of my end. But that's business for you.'

Giraud felt his skin crawl slightly, nervous goose flesh followed by a flush of embarrassment. Turning someone in and then stealing the jewelry from their corpse was either collaboration, or grave robbery, or perhaps a bit of both.

Still, he thought, I am just the messenger. I picked it up, I delivered it, I get paid. If I did not take the opportunity, someone else would. 'You have my money?'

'Of course. Here...' he took out his billfold and removed a thatch of large Franc notes. He licked the tip of his thick thumb and counted off two thousand. 'And the other matter? I take it you're still interested?' He handed the cash over, and Giraud secreted it within his wallet.

Francois had a new contact, an American who was smuggling cartons of his country's cigarettes in by the boatload. It was a risky venture, as the Germans had no love for the Americans, even though they had yet to get involved in the war.

'For sure, my friend, you know I can always take more,' Giraud said. 'Luckys and Camels?'

'And Chesterfields, and Marlboro filter tips for the women. I don't know, they all taste like shit to me,' the black marketer grimaced. 'Compared to Gitanes they are all like burning wet straw.'

'And yet, the demand....'

'Is very high, I know,' Francois said. 'I have one rule on these: no sales to Germans.' He tilted his head a little and took on a somber expression. 'The pressure

to snitch on their rank-and-file is exceptionally high right now and if one of them thinks they'll get ahead...'

'I understand.'

'Good. Besides, you will have no problem moving them.'

'I wonder...' Giraud began to say, before catching himself.

'Eh? You wonder what?'

'It's nothing.'

'No... come on, out with it.'

Giraud had been wondering about the wife, the woman who had owned the broach. Her husband had been shot trying to prevent the Nazis from taking her away. She had likely gone to one of the internment camps around the outskirts of the city. He had visited the one in Saint Denis and, though the Germans had kept him at the gate, had seen the undernourished, gaunt prisoners in their striped wool coats and trousers. Obviously they were being worked hard, and Giraud had little doubt that was why they were collecting so many Jews and communists, for labor, probably back in Germany

But it was not the kind of concern to raise with Francois. If he suspected Giraud was getting cold feet, he might find a way to remove him from the supply chain, the policeman knew, and that could be violent, or politically ugly, or likely both. In a city where the black market was a necessity of life, men like Francois who rested near the top held a certain sway, at times even over the Nazis.

And so he invented something, instead, to allay Francois' fears. 'I was just wondering whether your American friend could get hold of phonograph records. You know: the kind our gracious visitors from the east claim to hate.' It had only occurred to him in the moment to pick records, but like most things American, their music fascinated both the French and Germans.

'That... is difficult. The fragile nature of them...But I will certainly inquire. There is no harm in that. That's it? If you want I can line you up some premium girls, really clean...'

'No, that's fine.'

'Okay.' Then Francois frowned, maybe worried he was being judged, perhaps revealing frailties of his own. 'Someone already groomed them; I'm not pimping if that's what you're thinking.'

'I don't care, really.'

'Good. Because it's just business, like your records. You need anything else?'

Giraud could not help himself. He was not sure why. He refused to believe it was due to the troubles of people he did not even know; nevertheless, the question arose from his lips. 'Do you know what happened to her? The wife?'

Francois stared hard at him, perhaps looking for a reaction, gauging his reliability or at the very least, his cool exterior. 'I believe they took her away right after they shot him in the head, but I wasn't really paying attention to the details,' he said. 'I'm a fence, Giraud, not a crime reporter. Look, if it makes you feel any better, I understand they were an old family, with connections. I don't like it any more than you do, but if I don't move the piece, someone else will. Doubtless, they will work their other issues with the authorities and get their daughter home. But if you ask me, getting involved would be extremely foolish. Am I clear?''

Giraud smiled as sincerely as he could, but it wasn't easy. He suspected that the longer the Germans took to win the war, the harder it would become to look at the bright side of such things. He had always considered himself a romantic, unlucky in love but appreciative of its power; and it was only love that would drive a man to fight the Nazis at his own doorstep.

'Sure.'

'Good. You know, before the war I was a tailor. You wouldn't believe it, but these hands are magic with a tape measure and chalk. Still...' He looked reticent for a moment before shaking it off. 'Life goes on. For most of us, anyway. I have a family to feed -- two young boys, one with a palsy leg. My wife, she deserves better, but...

Giraud wondered if the Jewess had deserved such affection, such a struggle on her behalf to the very bitter end. He felt the weight of the money in his wallet, and he hoped it was not the case.

Caroline put down her wine glass and stared at Vaillancourt like he'd just sold their apartment for magic beans. They were having a late lunch.

'So what exactly are you saying, my love? Because telling me 'it's either a German officer or a French policeman' sounds like the kind of case that -- given its relative insignificance and the subject matter -- might well be avoided with the proverbial ten-foot barge pole. You're not really going to pursue this, are you?'

Vaillancourt sighed. She'd prepared a marvelous meal of pigeon pie -- liberally spiced with lemon and savory to make it taste more like Chicken -- and desert as well, a butter tart. She'd put on her old red cocktail dress from when they were young.

And now he was going to start an argument with her.

He supposed that if he'd really thought about it each time such a disagreement arose, he'd have found a way around the dispute, something witty and distracting that would allow him to preserve the integrity of his position.

'It's not up to me. We're getting pressure from the German High Command...'

'Oh pish!' she admonished. 'You know full well that if you find one of their own smuggling, they'll make at least one of you disappear, and quite possibly both; or, at the very least, they'll have you demoted to traffic duty at the arch.'

He shrugged. 'Would that be so bad? I'm forty going on two hundred and twelve, my love. I have to take on something less taxing at some point.'

She sipped at her wine then put the glass down. 'Yes, but there may be better ways to go about it, I suspect. Ones that don't involve widowing your poor, underappreciated wife.'

'If I died, I'm sure half the men in Paris would line up to replace me as your paramour...'

'Doubtless,' she said with her usual poise. 'But rich men make love like machines and poor men cannot be faithful.' Then she frowned. 'Hmmm. Rich men, too, I suppose. At any rate, I must make do with the lowly pension of a quite magnificent police inspector. And even though your salary is not expanding and your belly is, I do rather love you.'

'I brag about you at work, you know,' he said.

'Really?' She brightened.

'No, not really. My apathetic colleagues are not exactly scintillating conversationalists. One of them even likes the Nazis, but I can never remember which, so conversation is fraught with all sorts of peril.'

'Ahem. Getting the conversation back to the matter of peril...'

'Very smooth.'

'Thank you. Getting back...'

'You're welcome.'

She glared at him. 'Shut it for a minute, inspector.' She rose from her chair and moved over to his side of the table, then plopped down suddenly on his lap and threw her arms around his neck for support. 'I am issuing a Vaillancourt family edict. While we continue to strive to impregnate my obviously non-cooperative womb, you shall continue to strive to not have your head blown off. So, if you have to pursue both angles...'

'Both...'

'The Germans or a French policeman.'

'Ah, yes.'

'Then I implore you, start with the latter, my dear. Or...' She squeezed his neck gently with both tiny biceps; '... I shall throttle you like you were Uncle Adolf holding up a ration line.'

'Wise investigative advice,' he said. 'You know... if it gets you to release my carotid artery in one piece, that is. Still... I did find out something interesting today.'

She got up and grabbed the wine bottle from the center of the table, bringing it back to her chair as she sat down, then refilling her glass, before returning it to its spot on the red-and-white checkered tablecloth. 'And what is that, my love?'

'You remember I told you about a guy I went to school with? He sort of set me on my own course, if you will...'

'I do. I don't remember the details, but that was a long time ago.'

'Damien Giraud.'

'Yes, but of course. You were quite cryptic about it all, if I recall correctly.'

'It was a poignant and painful period in my life,' Vaillancourt said. 'In any case, it turns out that he's in charge of property disbursement for the Germans up in Saint Denis.'

'Let me guess: also the suspected source of your contraband

?'

'Exactly; or at least, that's what my kiosk-owning stool pigeon believes. And I believe I gave you enough information to recognize what an ...interesting guy Giraud is.'

'You've told the German High Command already?'

'Not about Giraud, but about Saint Denis as a source, yes. They want me to go up; it dovetails nicely with an investigation they've launched into resistance movements.'

'So: the matter is settled. Chase the policeman first.' She drained her glass. 'And if you have to, then the Germans. I don't suppose there's any point in my trying to get some life insurance on you, is there?'

'In wartime? I suspect not.'

'Hmmm,' Caroline said. 'Just as well. The way you snore sometimes, I might be sorely tempted.'

7...

It was just an hour from curfew when Giraud arrived back at his station in Saint Denis. It was one of the town's oldest buildings, three stories of grey stone, with narrow double windows in dark frames. It was imposing, which was fitting. They had blackout curtains on the windows to prevent any light from escaping but from close up, he could see the odd faint glow from inside. Though they were subject to curfew on their personal time, being a police officer on official business still held the advantage of working in the evening , when everyone else was supposed to be at home.

He was about to climb the front steps and enter when the doors opened and a familiar face walked out. He was short and portly, with a scrubby beard that could have just been a long period without shaving. His clothes and raincoat were wrinkled, as if he'd slept in them, and the tip of his fedora was bent too far forward, as if sat upon. 'I was wondering if you would ever come back to work today,' the man said, offering a hand to shake.

'And welcome, Inspector Vaillancourt. What brings my old colleague to our humble town on this brisk evening?'

'Hmm… business, I'm afraid, Damien. You know what I've been up to?'

He did. But Giraud often felt it best to exude a certain naiveté. It kept him out of some situations and gave him an advantage in others. He shook his head, 'I'm sorry, my friend, but my duties here keep me insanely busy.'

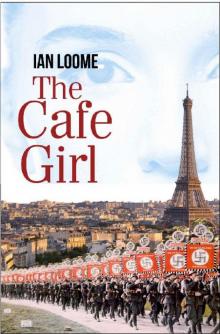

The Cafe Girl

The Cafe Girl